UX writing

1:1 interviews

Messaging frameworks

Content design

Content structures for human contexts

No building is free of context.

People’s dreams, hopes, needs and wants, instincts, fears, and priorities are contained within buildings and the landscapes between them. It’s useful to understand these circumstances, whether you’re trying to critique a building or sell architectural services.

Yet commercial architectural writing that describes the built environment through social, cultural, political, ecological contexts is rare. It shouldn’t be. Why should art criticism have all the fun?

For the architecture firm Ankrom Moisan, I prototyped, refined, and codified a new context-rich method of writing project descriptions.

Descriptions should be relevant to people.

Many of Ankrom Moisan’s profiles described each project as a kit of parts—square footage, materials, color palette, timeline, program intent, client request, that sort of thing—without showing relationships among them or explaining why each project was important to its users.

Readers had no real sense of why a building existed, how it might feel to visit, or how it responded to (and was influenced by) its site.

Find the why, the who, and the how.

MERGING DESIGN INTENT AND PEOPLE’S NEEDS

Following our newly launched brand strategy, I led an initiative to rewrite the firm’s project profiles according to its upgraded brand standards and a unified content framework.

For 40+ new projects, I interviewed dozens of architects and designers to learn who and what influenced their decisions, what challenges they faced, and how their visions took shape.

Since people were largely missing from the early project profiles, my questions focused on human experiences, emotions, and needs as well as site context, socioeconomic outcomes, and design methodologies.

I also focused on categorically understanding the needs, methods, outcomes, and insights of the disciplines involved in each project: architecture, planning, interior design, and brand.

FINDING PATTERNS

Next, I looked for shared patterns emerging from the designers’ responses.

In one 200-unit residential project, for example, the interior designers spoke of a need to convey openness, warmth, and calm to people transitioning from houselessness. The architects were designing with security in mind. These tensions led to expressions of Jane Jacobs’ concept of “eyes on the street,” with residents encouraged, through form and program, to watch out for each other in a safe and warm community.

By learning how two groups of designers expressed this insight, then joining their distinct methods into one coherent (and hopefully interesting) story, I was able to write a truer profile than by simply listing the building’s physical characteristics.

ALIGNING WITH BRAND STANDARDS

My framework-driven approach also explicitly connected each project profile to the firm’s new brand standards.

Architecture’s internal mission statement, for one, explicitly mentioned considering site with social context to serve people above all else. Such mutually accountable parameters served as handy relevancy filters during both the writing/editing and interview phases: If a designer or group wanted to discuss a tangental feature, we had our shared brand standards to nudge us back on the right path.

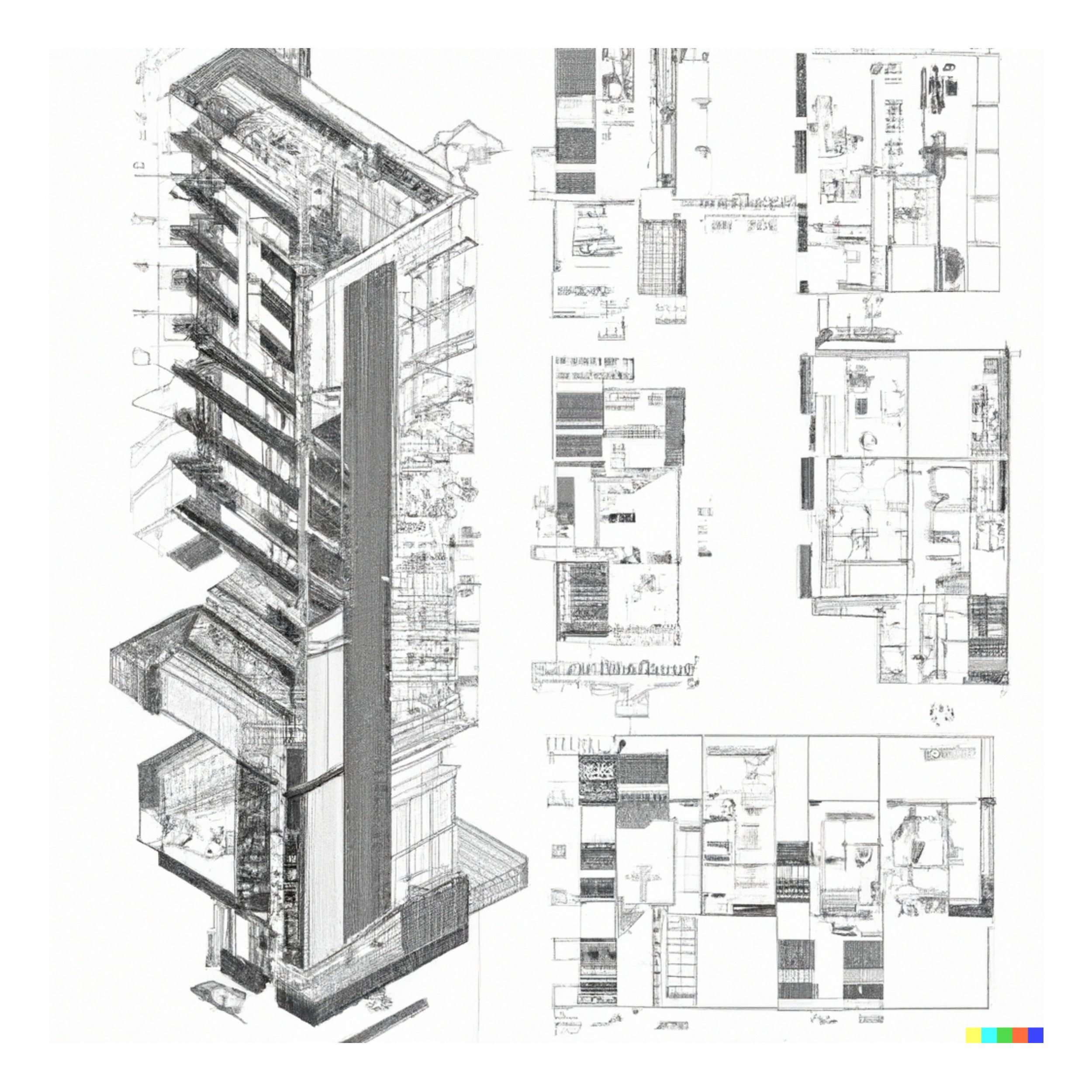

Along with my 1:1 interviews, photographs and digital renderings helped me further contextualize each project.

After incorporating feedback on each draft from project teams, I initially worked with our marketing director to edit and format each profile. Later, having tested and refined our approach on a handful of early profiles, I scaled up our production to lead a small team of writers.

Once finalized, each profile was uploaded to our content management system along with visual and design assets—one message expressed in both words and images.

Content systems can find the story.

Each new profile tells a fuller, more accurate, and human-centered project story and does so efficiently, using a templatized content-design framework.

An opening overview briefly establishes the design need, describes the project team’s methodologies and outcomes, and shares the overarching Why of each project: its insights and surprising-yet-inevitable conclusions. If a reader only read this section, they’d understand 80% of the project.

Discpline-focused sections follow, each following the loose structure of need-method-outcome-insight establishing in the interview phase. Since each discipline approaches a given project slightly differently, these sections give them a chance to shine while helping the reader understand the project’s contexts and human-centered expressions with more nuance.

Side benefit: It’s much easier for a producer to pull copy from these sections for discipline-specific social media posts, marketing content, case studies, and the like.

Deploying a standardized template and interview format made it possible for me to carefully scale up our content production as editor of a small writing team. While our face-to-face interviews played a central (if slow) role, by asking categorically similar questions for each project, we were able to move quickly from gathering information to synthesizing story insights.

Put people in the center.

Writing human-centered and contextually richer project profiles for a commercial architecture firm was less an intellectual exercise than a structural one. We didn’t need blood, sweat, and tears to pull storylines out of each project team. The storylines and insights were there.

We just needed a solid design framework. We needed to ask the right questions in the right way. And we needed to tell stories centered on people—about how a building served them, how it made them feel and think and behave—with built environments as supporting actors.